The human brain evolved outdoors. It was made to notice passing distractions, evaluate priorities, and become fully absorbed in the objects worthiest of our attention. Evolution favored early humans who could successfully scan the landscape and follow sparks of instinct, like reading a compass pointing true north – except the needle pulled them toward a primal understanding of the world.

Likewise, kids’ senses are built for capitalizing on interactions with their environment to bolster their development. Children are natural prodigies of untamed, unstructured experience. When they are given outside play time without an agenda, they transform into their best selves. Exploration begets discovery. As they immerse themselves in the physical world by climbing trees and observing ant hills they gain valuable insight, most of all about themselves.

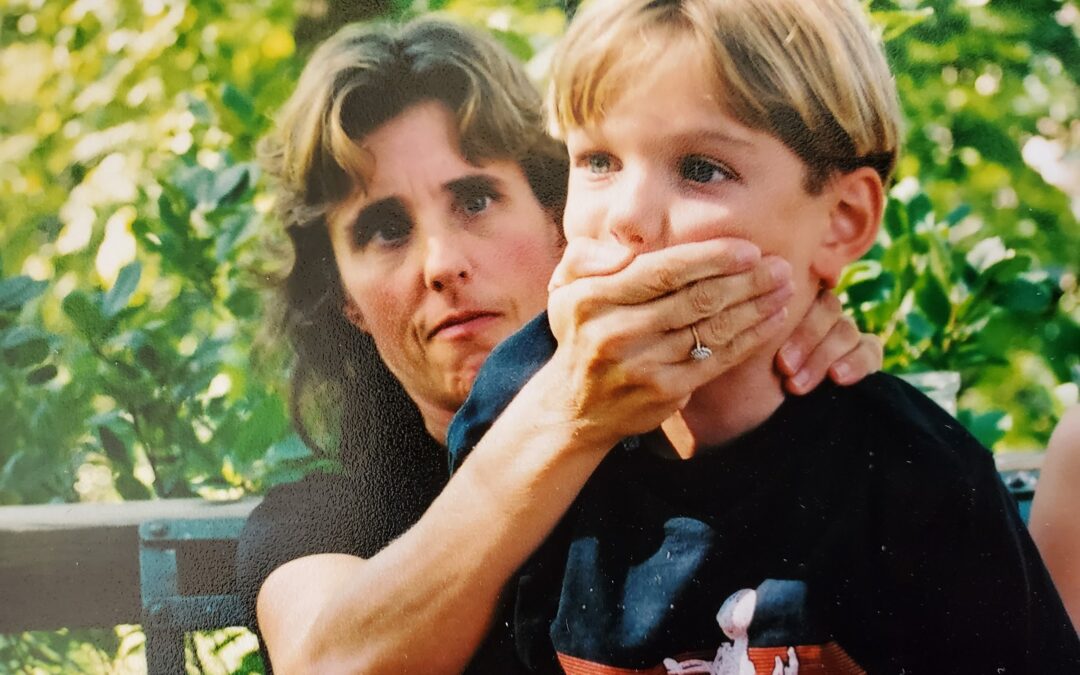

Anyone who has watched a child indulge their innate curiosity without adult intrusion has seen the beautiful intensity of this phenomenon. You can actually see growth unfolding in real-time. But why does it seem to be so particularly powerful outside in the wilderness of our backyards, parks, and forests? One answer is as mystical as it is simple.

We exist, now and always, as beings made up of the same matter as the rest of the ecosystem. We can only understand ourselves if we’re able to see ourselves reflected in the giant and unfathomably entangled web of other beings. Learning to relate to nature – following animals and insects with our eyes, our hands, and our hearts – allows us, simply, to become ourselves…by becoming one with them.

The most recent results of cognitive research show with scientific authority what we feel in our souls: the growing brain needs this ‘other,’ a partnering incarnate subject that consists of living matter, for healthy cognitive and emotional development. To put it more poetically, children need their gaze to be returned by the surrounding aristocracy of life in order to effectively tap into their own depths.

Unfortunately, our modern society appears determined to pull kids away from both the visceral connection to each other and to the wilderness waiting outside their door. Technology beckons for their attention with ever more seductive hooks to their brains’ reward centers. According to recent Gallop data, by the age of 8, children spend up to a whopping six hours of screentime a day.

The deviation from time spent in our living and breathing outdoor environs to a flat, virtual world is stealing more than just emotional self-awareness from kids. It throws salt in the wound by disabling their capacity for sustained engagement as it becomes constantly punchier and more stimulating, feeding young brains their next addictive fix within milliseconds. The beckoning forest doesn’t stand a chance

Young kids’ neurons are exploding in a million different directions and looking for interrelation. Space to run free in nature actually helps them develop better brain machinery. Juvenile rats who are restricted from play in wide open spaces fail to fully develop their frontal lobes (which control executive function) and have impulse control and social interaction problems. However, rats given just 30-minute unrestricted play sessions released brain growth factors and activated hundreds of genes in the frontal cortex.

If that’s not convincing enough from a brain-body standpoint, here’s some more compelling evidence for you: kids who spend more time in nature also tend to sleep better, have elevated attention and problem-solving skills, host healthier internal microbiomes, enjoy more robust immune systems, and develop overall stronger and more agile physiques.

So what’s a concerned parent, grandparent, or caregiver to do? The solution need not be complex or intimidating. Simply begin by getting your kids outdoors (and join them when you can – benefits exist for you, too)! Encourage them to take walks, dig holes in your yard, and get dirty. Give them regular opportunities to experience the freedom of being set loose outside. Respond to the “I’m bored’ declaration with the suggestion of a wild adventure. It’s really that easy!

Encouragingly, some societal shifts are also occurring to help out. The number of nature-based preschools and primary schools is growing, and more companies are forming to provide ways for families to reconnect with nature. Traditional summer camp registration has seen huge surges in enrollment since 2021, and many of them offer family stays. Getaway House, a burgeoning business launched in 2015, makes it easy to leverage family vacation time by renting out fully-equipped tiny cabins set up in the woods all around the country, for essentially the same cost as a hotel room.

It’s a worthy cause. The effort to get kids outside has big payoffs. When children are left to their own devices to roam in nature as in generations past, they learn to see themselves as part of a great, magical universe. They shed their self-conceit and experience the fragile interrelatedness of all life. Best of all, they nurture their capacity for empathy, care, and kindness – exactly what this world needs, now more than ever.