The Kid In The Mirror

Whenever we catch our reflection in a mirror, we hope to see good stuff reflected back. If we’re ok with what we find, we might sneak an extra peek. It feels great to experience affirmation about the best of ourselves. It’s not really vanity or narcissism. Just an innocent and normal desire for reassurance.

In fact, that desire goes well beyond physical appearance. We all want to know that our ideas and opinions are valid, so we seek out places they’re reflected back to us positively. Technically, it’s called confirmation bias. When other people feel what we feel and think what we think, we can breathe a sigh of relief. Phew, we got it right!

Whether with politics, ethics, status (money, degrees, job title), or culture (music, art, literature, diet, fashion), we often look around us to find out if we’re on the right track with our decisions. When we’re feeling disordered inside, it’s especially appealing to find reflections of our understanding that can help settle us down.

With kids, however, this process is largely unconscious and nonstop – babies all the way up through teens are in a constant state of refining their core understanding of themselves. It’s like living in a room full of mirrors.

When I was young, the validation I sought out wasn’t always reliable or available, so I found it wherever I could. I had an idea about what relationships should be like, and I attached myself to shows and movies that confirmed my expectations. I was a deep thinker and sensitive kid (in other words, I often felt like a weirdo), so I became drawn to books with characters who fought solitary inner battles and prevailed with quiet cunning and wit.

I crafted my own self-perceptions without an official roadmap and few personal guides. Most of my reflections came from self-selected books and media, which was fairly limited in the 1980s. Today, our kids are drowning in social apps and pop culture influences, whether they ask for them or not. Algorithms lure them down numerous questionable paths that feed them endless material.

While I could curate my own influences and strategically shape my identity through gradual developmental stages, kids these days are at risk for having their sense-of-self engineered at an addictive level. Taking away their screens doesn’t scratch the surface.

It’s normal for parents and educators to want to steer the media narrative, but it’s usually a losing battle. The onslaught is becoming too big and insidious. This is where the mirror concept becomes useful. Because kids typically seek reflections that match what they feel about themselves, caregivers can lay the groundwork early to help them see themselves as responsible, grounded, and thoughtful people. In this way, they’re empowered to act as their own best filter.

Here are some ways to guide them:

- Name and support their natural strengths – particularly the ones that aren’t always noticed by others.

- Help them to notice and highlight the natural strengths in everyone else around them.

- Model optimism and proactive problem-solving, even when the odds are stacked up.

- Create ways to let them use their unique gifts to make other people’s lives a little bit better.

- Teach them to think of mistakes as opportunities for learning, rather than a cause for shut-down.

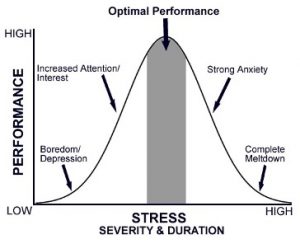

- Normalize, describe, and let them sit with big feelings – especially the uncomfortable ones.

- Provide them with chances to apologize, repair, and grow from any damage they may cause.

- Encourage them to forgive others and seek to understand why other people behave the way they do.

Our kids develop their self-image based upon the reflections that are around them. Luckily, the most powerful ones will always come from the adults in their lives they love and who love them back.

About the Author

Kerry Galarza, MS OTR/L is the Clinical Director and an occupational therapist at Elmhurst Counseling. She provides specialized assessment and intervention with children of all ages and their families. Kerry engages clients with naturally occurring, meaningful home-based methods to empower autonomy and maximize functioning.